This content has been archived. It may no longer be relevant

Less is said, however, about the range of tools many countries in the region are deploying to include some of those furthest behind in mainstream schools: students with disabilities.

These efforts should be celebrated and there seems a no better time to think about inclusion than now. Inequalities in education are always blatant, but the new 2020 Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report by UNESCO shows that the Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated exclusion. About 40 percent of countries in sub-Saharan Africa have not been able to support disadvantaged learners during school closures, notably students with disabilities.

Prior to the pandemic, countries in the region were taking different approaches to inclusion. Data from the continent shows that 23 percent of countries have laws calling for children with disabilities to be educated in separate settings. Most countries, however, combine mainstreaming with separate arrangements, usually for learners with severe disabilities.

Many of the countries looking to move from segregated towards inclusive systems need to overcome management challenges. They need to think how to better share specialist resources between schools so that all children can benefit. Examples of this can be found across the continent.

Angola and Nigeria, for instance, are looking at transforming special schools into support bases for children with disabilities in mainstream schools, as well as providing training for teachers. Angola set a target in 2017 of including 30,000 children with special education needs in mainstream schools by 2022.

Kenya also recognizes special schools’ pivotal role in the transition towards inclusive education. At present, almost 2,000 primary and secondary mainstream schools provide education for students with special needs.

Malawi tries a twin-track approach. Those with severe disabilities are educated in special schools or special needs centres, while those with mild disabilities are mainstreamed. Special schools at each education level are being transformed into resource centres.

Instead of resource centres, Tanzania is mobilising itinerant teachers offering specialist services. These teachers are trained and managed by Tanzania Society for the Blind and provided with a motorbike. They also perform vision screening, refer children to medical facilities and organize community sensitization and counselling

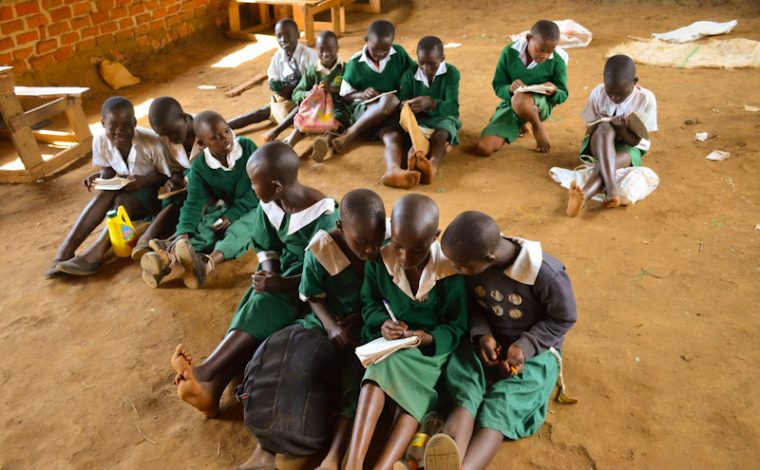

While the political will for change seems clear, there is often a gap between theory and practice. This is where the emphasis between now and 2030 must lie. Throughout sub-Saharan Africa, teachers mention that implementing inclusive education is hard because they lack resources.

Take Malawi for instance. While it is increasingly encouraging learners with special needs to enrol in mainstream schools, a lack of facilities forces many to transfer to special schools. In Namibia, the shortage of resource schools in rural areas, a lack of accessible infrastructure and unfavourable attitudes towards disability are just some of the barriers to successfully implementing its inclusive education policy. Similarly, in the United Republic of Tanzania, only half of children with albinism complete primary school. Because they lack support, they often end up being transferred to special schools.

The same story can be found in South Africa. It has a law from 1996 stating that the right to education of children with special needs is to be fulfilled in mainstream public schools. But recently it reported back to the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities that it had new segregated schools in basic education and a lack of provisions for children with severe intellectual disabilities.

Ghana is another case. It is the only country in the region to make provisions for all learners in its education law. Its 2015 inclusive education policy framework envisages transforming special schools into resource centres, while maintaining special units, schools and other institutions for students with severe and profound disabilities. But children with intellectual and developmental disabilities must perform the same tasks within the same time frame as their peers without disabilities, occupy desks placed far from teachers and are often physically punished by teachers for behavioural challenges, even in inclusive schools in Accra.

While all these efforts are commendable, simply laying the groundwork for inclusion in education will not suffice. Implementing the ambitions spelled out in education policies will take a new wave of efforts. The 2020 GEM Report looks at the different steps needed to provide disability-inclusive education, providing ten recommendations for policymakers, teachers and civil society over the next ten years. We hope it will prove a useful resource for countries in the region to move to the next stage.

Manos Antoninis is the Director of the Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report, UNESCO

1 Comment

Pingback: Intel Ties up With Jesuit Worldwide Learning on Skills Training