Article 27(8) of the Constitution of Kenya 2010 provides that the State shall take steps to ensure not more than two-thirds of members of all elective and appointive positions are not of the same gender.

Ten years after the promulgation of the Constitution of Kenya 2010, there is yet to be enacted a specific legislation to operationalise this constitutional provision on gender equality.

Consequently, the Kenyan Parliament has been wrongly castigated for failure to enact the relevant legislation.

The high-level criticism levelled against Parliament is somewhat misplaced in my considered view, for a variety of reasons: To begin, it is the State that is empowered to ensure two-thirds of members of all elective and appointive positions are not of the same gender.

As a concept, the State is a form of political community and refers to a conglomeration of various organs.

The State must be distinguished from the government, which refers to a group of people who are usually in charge of state apparatus. The various arms of government include the Executive, Parliament and the Judiciary as well as Independent Constitutional Commissions.

It is therefore the State as a broad entity that is vested with the obligation to take measures towards ensuring gender parity. An understanding of the entire law-making process indicates that it is not solely upon Parliament to have a law enacted. Bills may originate from anywhere including from the public, subsequently processed through the House and then finally presented to the President for assent.

Already, there have been a number of initiatives towards this end that have attempted to amend the Constitution of Kenya 2010 to provide for top ups through nominations of persons of the least represented gender or even to scrap the two-thirds gender rule contained under article 177 of the Constitution with respect to county assembly members altogether.

However, all these efforts have not succeeded in Parliament.

More importantly, there is no express constitutional edict directed at Parliament requiring it to pass legislation to ensure compliance with the two-thirds gender principle with respect to MPs.

While this is provided with respect to Members of County Assemblies under article 177 and 197 of the Constitution which expressly require the creation of special seats to ensure compliance with the gender principle, there are no such mechanisms provided for with respect to Members of Parliament.

Admittedly, nothing would have been easier than for the Kenyan people to have expressly provided for such mechanisms in the Constitution as they did with respect to Members of County Assemblies if at all they desired Parliament to bear the responsibility of passing such legislation.

The obligation to take measures to ensure two-thirds principle in all elective and appointive positions as provided for under article 27 of the Constitution is on the State as a body rather than Parliament as a single institution.

This interpretation is further confirmed by the fact that the two-thirds gender rule with respect to Members of Parliament is not one of the pieces of legislation envisaged under Article 261(1) in the Fifth Schedule of the Constitution. The relevant Fifth Schedule in fact makes no mention of any legislation to be passed by Parliament arising from article 27 of the Constitution upon which Parliament has been blamed so harshly.

Aptly put, therefore, it is not the case that there is an express command by the Constitution on Parliament as a body to pass a two-thirds gender rule with respect to Members of Parliament.

The other direct and express constitutional obligation on Parliament to pass legislation relating to promotion of representation of women, among marginalised persons, in Parliament is to be found in Article 100 of the Constitution.

The relevant provision provides that ‘Parliament shall enact legislation to promote the representation in Parliament of:

a) women;

b) persons with disabilities;

c) youth;

d) ethnic and other minorities; and

e) marginalised communities.’

A keen reading of this provision means that the only direct obligation on Parliament is passing a law that ensures that all these marginalised groups including women are represented in Parliament. But there is no mention of particular proportions that are set out as is the case with article 177 and 197 on Members of County Assemblies.

Accordingly, any court battle relating to the passage of legislation to ensure the representation of women in Parliament can only be founded on Article 100 of the Constitution and not article 27 as has been argued.

Relatedly and in any event, we have not witnessed the same energy directed at other public bodies and state agencies and constitutional commissions that are either elective or appointive even where they are not gender compliant.

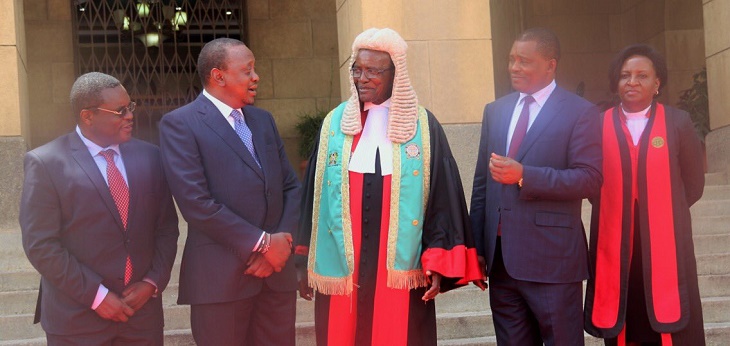

Despite the huge attention that has been placed on Parliament, gender parity compliance on the part of the Executive especially the Cabinet, Judiciary including in the Supreme Court and other key state agencies has not been met.

In particular, the Law Society of Kenya Council, which is an elective position of lawyers and which regulates the profession is currently not compliant to the two-thirds gender principle.

Further, the State also refers to the polity or the electorate or the sovereign who are the people. It is incumbent upon the people in exercise of their sovereign will through the ballot to give effect to the constitutional provisions on gender parity by ensuring they vote in their representatives to ensure compliance with respect to elective offices. It then falls upon the Executive to ensure compliance with the gender parity dictates in appointive offices. A significant part of compliance required with respect to various elective and appointive positions does not necessarily require specific legislation enacted by Parliament.

The larger problem is structural in nature and also on account of lack of necessary goodwill. It is therefore somewhat misplaced to place the blame entirely on Parliament for failure to achieve gender parity in various elective and appointive positions.

It is also disconcerting that the clamour to pass legislation to ensure two-thirds gender principle potentially violates the sovereign will of the electorate at least to the extent that such legislation will demand top ups or nominations of women. Excepting the cost implications, this is akin to fundamentally skewing or altering the sovereign will of the people who go to the ballot to elect their representatives in a constitutional democracy. One of the chief roles of MPs is to make law, approve budgets and check on the Executive.

Legislators exercise their legislative and oversight functions through voting. At present, if we were to nominate women legislators to comply with the two-thirds gender principle in Parliament, we would have to nominate up to 100 women legislators.

Given that legislators decide through voting in Parliament, this would in essence mean that there are an additional 100 votes of nominated women legislators, yet these legislators are not a direct expression of the will of the people.

That elected legislators wield more legitimacy relative to nominated legislators can be deduced from article 123 of the Constitution with respect to voting in the Senate. In the said provision, while all Senators who were registered voters of a particular county during elections constitute a single delegation for purposes of making decisions in the Senate, it is the elected Senator of the particular county who is usually the head of such delegation.

What is more, is the elected Senator as the head of delegation who usually has the priority in voting on matters affecting counties and under the Senate Standing Orders, the head of delegation can refuse to delegate voting to another member of their delegation. This impliedly demonstrates the supremacy of elected Senators, principally on account of being directly elected by the people.

There has also been an argument to the effect that the High Court sitting in a constitutional petition in Petition No. 317 of 2016 already called for the dissolution of Parliament if it failed to pass the relevant law within 60 days of the judgment. The said judgment was issued on 29th March 2017 and it has been over three years since.

However, it need to be clarified that the said decision was directed at the then Eleventh Parliament whose term ended after the General Elections in 2017.

The judgment provided that any person could petition the Chief Justice to advise the President to dissolve Parliament if the relevant legislation was not passed within sixty days. But the term of that Parliament expired upon General Elections in August 2017 and a new Twelfth Parliament, which is the current Parliament, assumed office. While Parliament is a body that enjoys perpetual succession, it is made up of individual members some of whom are not usually re-elected.

Accordingly, there is no live court order directed against the current Parliament as to kick-start the process for dissolution of the current Parliament.

In any case, the clamour for dissolution of the current Parliament on account of failure to enact the two-third gender legislation is at the very least, unrealistic. There is nowhere in the current Constitution that the onus is placed on Parliament as an institution to ensure there is gender parity in State organs. In fact, dissolution of Parliament will necessitate a by-election in all constituencies, nearly akin to a General Election.

Even more fundamentally, there is o particular guarantee that were byelections to be conducted throughout the country under the extant First Past the Post electoral system, the obtaining

electoral results would be gender compliant. This is especially the case since the factors that have contributed to few women being elected into office such as high cost of campaigns, electoral violence and cultural attitudes have not yet been eliminated.

Given the current efforts and initiatives to amend the Constitution that are currently underway such as the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI), the issue on two-thirds gender rule can be subjected to a referendum in the event the same happens. Owing to the cost implications of implementing the two-thirds gender rule through other mechanisms such as nomination and topping up, it is prudent if the matter were to be subjected to the people once more for a reevaluation or to propose ways of achieving two-thirds gender rule.

Importantly, various electoral laws may need to be amended as a consequence of Constitutional changes in order to align the statutes with what could be the outcome of such a vote.

They include the Elections Act, the Political Parties Act, the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) Act and the Campaign Financing Act. We must not lose sight of the real challenges in implementing this matter and turn Parliament into a punching bag on account of gender parity.